Dear reader,

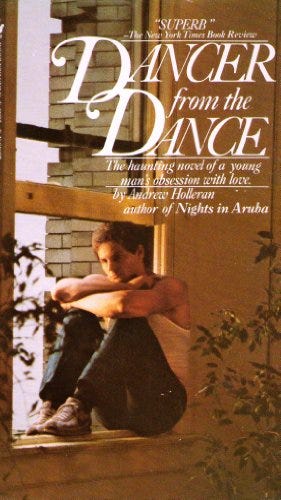

By the time you read this, I’ll be nearing the end of two weeks stuck in self-isolation in Halifax. It’s been a reader's dream, in a way, to have 14 days to myself to stop and think. And apart from a few moments of doomscrolling-induced madness, I’ve been using the time productively. I’m hard at work on a book proposal, and have been making my way through a stack of books that directly and indirectly complement my research. There’s something almost magical in slowly tracing a history, seeing how different texts are in conversation with each other, finding where they connect and diverge, and following rabbit holes in search of something intangible. It hasn’t really felt like work, either. Some of the books I’ve been reading for research have been pure pleasure, like the 1978 novel Dancer From the Dance by Andrew Holleran, an enmeshed part of the gay literature canon (alongside works like Larry Kramer’s Faggots, released that same year) and a fine novel in its own right.

It’s no secret that since well before the dawn of gay liberation — and even sometimes to this day — the plot trajectory of the average gay novel (at least in the popular imagination) has been one that ends in death. From classic works of gay literature like Giovanni’s Room (1956) to more recent cannon fodder such as A Little Life (2015) gay life and tragedy have often been inextricable. The debate over this has been happening for so long now, that though fair, it’s begun to feel a bit stale, with the argument going something like this: if the only stories told about us show that our lives are in peril, and that there are no happy outcomes for us, what does that tell young queer people seeing themselves in stories for the first time? Speaking only for myself, it probably doesn’t tell them anything they haven’t already heard.

But the question remains, if you’re a gay writer yourself, and want to tell a story that does — like life — have pain and joy, how do you dodge this criticism? One way of doing so is to follow Holleran’s lead and get ahead of it. In Dancer from the Dance, he begins by sharing a metafictional correspondence between the “author” of the novel we’re about to read, who like Holleran is based in New York City, and a friend who has moved away from the whole scene and put down roots in Florida. The author tells him that he’s written a novel and hopes he’ll read it. But his friend cautions him against writing a gay novel and warns that straight audiences would “puke over a novel about men who suck dick (not to mention the Other Things!)” and perhaps as a consequence, “they would demand it be ultimately violent and/or tragic, and why give in to them?”

Indeed, Dancer from the Dance is ultimately a novel steeped in tragedy and violence, but it’s also indelible, and at times even, sublime. It follows Malone and Sutherland, two “doomed queens” careening their way through gay New York. Malone is a formerly buttoned up lawyer who sheds his career and family in his relentless pursuit of love and sex, while Sutherland is a veteran girl-about-town, leading the way for Malone and offering him his first glimpse into this world of desire and impulse. From circuit parties, to all-night revelry at packed discotheques, to cruising at bathhouses and city parks, and seasonal parties on Fire Island, it’s a charming glimpse of Rome before the fall. Set in the 1970s, it’s both a celebration of gay liberation and a subtle critique of it. Our characters chase after love, and in the absence of it, bury themselves in bodies. “They were bound together by a common love of a certain kind of music, physical beauty, and style,” writes Holleran. “All the things one shouldn’t throw away an ounce of energy pursuing, and sometimes throw away a life pursuing.”

Of the two main characters, Malone is the more sympathetic one, while Sutherland comes across as a more complicated character. In Malone we see the trade-off so many gay men of this era made, between their families and their sexuality, between living a life devoid of pleasure and a life seeped in it. “He did not wish to be a man to whom nothing was ever to happen,” writes Holleran, of Malone’s fateful decision to cut ties with his old life. “He was completely free now to pursue with the same passion for success he had brought to squash matches and the law, the one thing that had eluded him utterly until now: love.”

In Sutherland, we see someone who knows, for better but mostly for worse, exactly who he is. After Malone escapes an abusive relationship, Sutherland takes him in, acting as both his den mother — and in time — his pimp. Having been in this world for long enough to count as an elder, there’s lots that Sutherland can show Malone, including granting him access to the dizzy world of the disco, where men chase “the next song that turned their bones to jelly and left them all on the dance floor with heads back, eyes nearly closed, in the ecstasy of saints receiving the stigmata.”

But Sutherland is also a stone cold racist, casting judgement on latinos, blacks, and any race that deviates from his WASP ideal. “Of course he beat you,” he tells Malone soon after they’ve first met. “Let it be a lesson. This ethnic gene pool in which we sit, like children in their own shit.” Reading this is bracing, and I would understand if a line like this is enough for some readers to slam the book shut. But it does bring up that age old question, which is what do we want from literature? Do we want authors to be circumspect? For a narrative to come attached with an easy moral lesson? Or do we want something more conflicted, more messy, perhaps more real.

In a 2015 interview, Holleran described his book as a critical satire: “I was trying to portray the harshness, the bleakness of gay life, of a life based really on aesthetic values where it was all about beauty and pleasure.” And undoubtedly, racist queens like Sutherland did and still do exist. It’s not pleasant to read about them, but it is illuminating. Ultimately, it’s up to readers to decide, but there’s a reason the book has endured since it was published, and part of the reason is that it doesn’t lack for punches.

As the novel goes on, both characters continue their fall. Malone searches for love to no avail but remains hopelessly addicted to the search. “He made love at rush hour in men’s rooms of subway stations; he made love at noon, at midnight, at eight in the morning; and still he found himself alone,” writes Holleran. Meanwhile, Sutherland begins to long for an escape from the fastlane and decides his best option is pimping Malone out to the highest available bidder. “He who had been raised to consider money slightly vulgar suddenly wanted, now that the illusion of love gripped him infrequently, material things: He wanted a house in Cartagena, he wanted to go to Rio if he cared to. He wanted to be able to leave New York from time to time, and not to have to be nice to people in exchange for it”

It’s just as ugly as it sounds, but reading this book in 2020, I couldn’t help but feel moved by the characters, knowing what’s ultimately to come. It acts as an inadvertent elegy to a lifestyle that unbeknownst to its participants and author was soon to be forever changed with the advent of AIDS. Within 10 years, many of the men Holleran writes about would already be sick, or worse — dead.

Still, at the close of the novel, the plague is a ways away. For so many of these men, all that matters is the present. This song. That body. The night. In the end, Malone goes AWOL, but not before attending one last rager on Fire Island, where his essence, to me, is crystallized. “On his face was an expression of radiant exhilaration; that expression that led people to think Malone took speed, when he didn’t. It was just his joy that there were men who loved other men.” In between the pain and sorrow, sometimes that’s enough.

Until next time,

Andrew

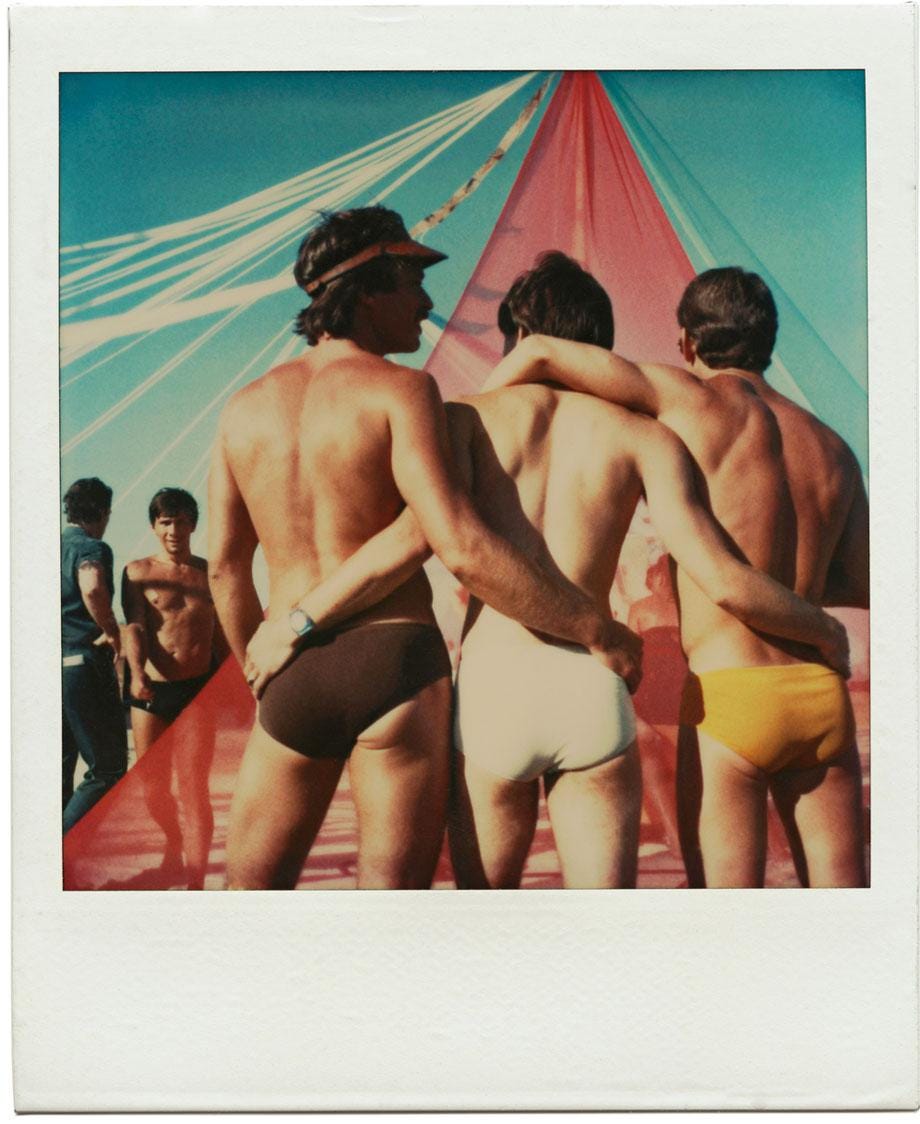

*The opening image of this newsletter is by Tom Bianchi, whose photo also graces the cover of the most recent edition of Dancer from the Dance. He’s a photographer who chronicled much of the scene Holleran wrote about in this book. Among other publications, Bianchi is the author Fire Island Pines: Polaroids, 1975-1983,